MILAN, AN EUROPEAN METROPOLIS

Milan: a rich city, a great metropolis at European level, for Jewish people the second Italian community (the first is in Rome). Jews were allowed to live in the city only in the early 19th century, before that they were not allowed to stay there for more than three days. Not to be missed is a visit to the Central Synagogue at via della Guastalla 19, at the Library-Archives of the Center for Contemporary Jewish Documentation at via Eupili 8, on the ground floor a small oratory of the Italian rite, and the Memorial of the Holocaust (Track 21) in Piazza Edmond J. Safra 1.

A YOUNG COMMUNITY, TODAY COSMOPOLITAN

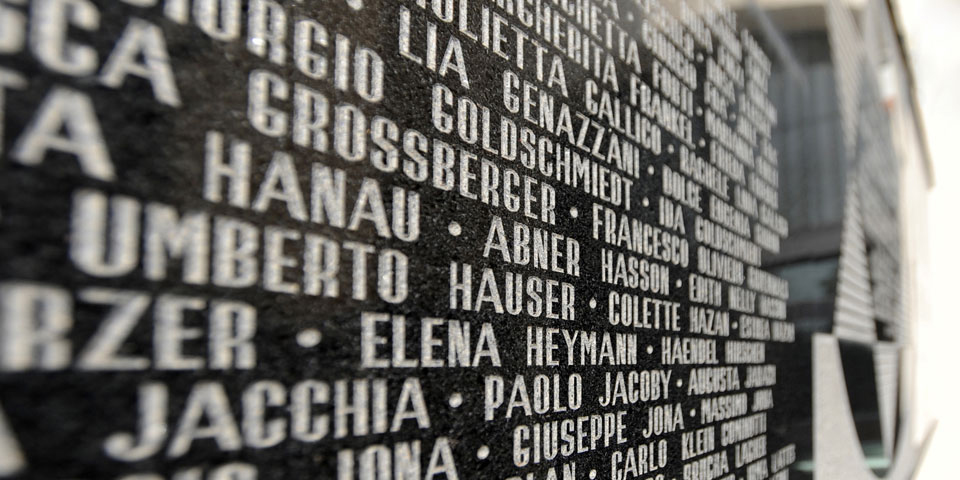

The community of Milan dates back to the 19th century. In the city, first the capital of the Duchy of the Visconti, and then of the Sforza, Jews had always been allowed to stop a maximum of three consecutive days to dispatch their business. For this reason they resided in nearby towns such as Monza, Abbiategrasso, Melegnano, Lodi, Vigevano, Binasco, and they went to Milan each day. This commuting was possible until 1597, when they were expelled. From that time, and for more than two centuries, there has not been any Jewish presence in the city and in the duchy. They returned at the beginning of the 19th century, as a section of Mantua, the only Jewish community that had always remained in Lombardy because of different rules. From that time, the group grew rapidly in number: seven family units in 1820, two hundred people in 1840, seven hundred in 1870. In 1866, Milan broke away from Mantua and constituted its own "Israelite Consortium". Jews joined it voluntarily and they undertook to pay the taxes for its maintenance. In 1890 the Jews were two thousand. They decided to build a prestigious synagogue in the heart of the city, in via della Guastalla. It replaced the small oratory at via Stampa 4, a room in the rabbi's house Prospero Moisé Ariani. The community continued to grow. The industrial development attracted Jews from all over Italy and Europe. In the twenties the Community had 4.500 people, eight thousand in the thirties. Because of the advent of Hitler many German Jews left Germany and took refuge in Italy. Italian Jews also came from Piedmont, Marches, Tuscany, and Veneto. Here the Jewish communities of small cities and rural areas were disappearing. In 1938, at the time of the promulgation of Racial Laws, the Jews were twelve thousand. Among these, five thousand managed to escape to Switzerland, Mandatory Palestine and to the Americas. The deportees were 896. Only fifty of these returned. Immediately after the Second World War, the group welcomed the refugees who survived the death camps, and it became an important center for illegal emigration to Palestine. From the fifties, groups of Jews expelled from Arab countries had arrived following the Arab-Israeli wars (the most numerous from Egypt, Syria, Libya, Lebanon, Iraq, Iran) and groups from Turkey, Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary. Today seven thousand Jews live in Milan, coming from fifteen different countries. Many of these have maintained rites, customs and traditions of the country of origin and they have autonomously organized themselves with their own prayer rooms (thirteen in the city, with Italian, Sephardic, Sephardic Oriental, German, Persian, and Lebanese rites). The new generations, Milanese by birth, who attend the same Jewish school from the nursery to the school-leaving examination, are starting a new Milanese Jewish group, culturally homogeneous.

AN IMPOSING SYNAGOGUE FOR FREE JEWS

The central temple "Hechal David u-Mordechai", at via della Guastalla 19, was planned by Luca Beltrami, a famous and well-known architect of the late 19th century. It follows the Italian rite. The project, following the eclectic culture, included Byzantine and Moorish elements. The area measured 1.150 square metre, with a street-front of 37 metres. Inside, an aisled scheme like in the churches. The aròn in the apse of the eastern wall, the tevà in front, a pulpit, and a platform for the organ. The architect also designed the façade, the only part of the building that has remained. It is divided vertically into three parts: the central one, larger, which corresponded to the nave of the temple, and the two lateral ones, that corresponded to the aisles and to the lateral tribunes. The central part was enriched by a large arch, with at the base the main front gate. Above the front gate there is a porch with three arches. At the top, the tables of the Law. In building the Community spared no cost. The Italian State lent 75 million Italian lire, repayable in thirty years, half of the final cost. The synagogue was solemnly inaugurated in 1892. In August 1943 a firebomb hit the building. The hall was badly damaged. In 1947, the Community entrusted the reconstruction to the architects Manfredo D'Urbino and Eugenio Gentili Tedeschi. They would have to completely rebuild the entire building, demolishing everything, including the façade. The latter was saved because of the high cost of demolition. The new building was finished in 1953. It turned out to be a typical example of "rationalist architecture."

In 1997 the building was profoundly transformed. The outer volume has remained unchanged, the façade has been restored, the street-front bordered by a wrought iron railing, and the central front gate has been rebuilt according to the Beltrami’s original drawings. The interior has been redrawn by Piero Pinto and Giancarlo Alhadeff. Brightness and colour are the main elements. Red and Gold dominate the room. There is gold in the bottom part, on which rests the large aròn, and the balustrade is also gold, and delimits the aròn and the inside of the dome. The ceiling of the room is white. The lateral walls have rusticated masonry, reminiscent of rough stone. The floor is made of red marble from Trani and of white pearly marble from Sicily. The seats in light beech wood (453 on the ground floor and 402 in the women's gallery) are covered with a dark red fabric. The twenty-three large windows, by the New Yorker artist Roger Selden, look like a great collage of symbols and Hebrew letters, repeated with different tones and shapes. At the back of the synagogue, the "Scola Shapira in Centro Nessim Pontremoli," also of the Italian rite, is used daily. It has 18th century furnishings of Fiorenzuola d'Arda, a vanished community in the area of Piacenza. In the basement there is Jarach room, for conferences and meetings, and the Sephardic Oriental oratory, with furnishings of Sermide, vanished community of the area of Mantua.